Rejections for February so far: 6

Total rejections to date for 2025: 15

If you want to learn more about the important role of rejection when submitting to literary journals (while also building your confidence in regards to the submissions process), check out my upcoming workshop: GO FISH! Jumpstart Your Literary Journal Submissions Game. (Click the link for more information or to register. Save $25 if you sign up by February 19!)

Building Blocks

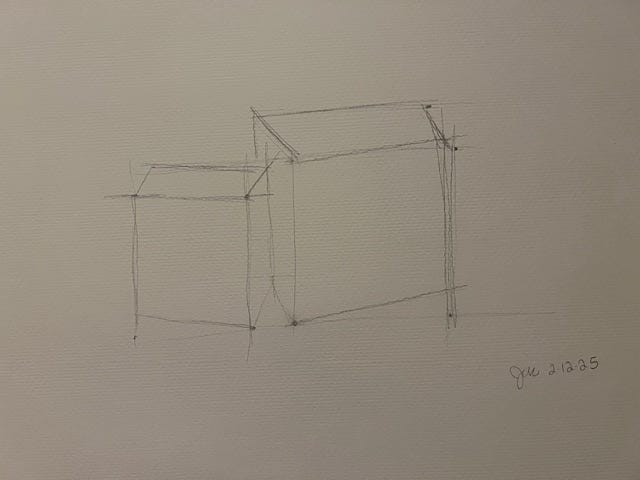

This week I had my first drawing lesson. The below photo shows the cubes/blocks I drew!

These are (literally) the building blocks to drawing; as my teacher told me, once you learn what she calls the “formula” for drawing, you can draw anything, and you can even draw with your non-dominant hand or your mouth!

I’ve dabbled in visual art as a creative outlet for most of my life, but aside from a few one-off painting classes here and there and public school art classes, I’m primarily self-taught. And I never really learned how to draw.

That is to say, I was never taught the building blocks of drawing.

I actually drew incessantly as a kid—probably more so than I wrote (and I wrote a lot!); my usual drawing subjects were my rather large crew of nearly twenty imaginary friends. These “imaginary friends” all had names, personalities, and intricate backstories, all of which I developed during the drawing process. In short, they were story characters, but the stories were visual. I did, however, also write a few “scripts” with these characters. When I was about seven or eight years old, my dad made me a “television” out of a cardboard box. It had a slot about the size of a 1980s-era TV screen for my drawings to slide into and a space behind to conceal a tape recorder. I made drawings that were essentially story panels, then wrote and recorded a script. Finally, I presented the “TV show” (usually a “holiday special”) to my family, who were all rather unimpressed; I vaguely recall my brothers joking about wanting to change the channel.

Imitation—the Sincerest Form of Flattery

So, how did I learn to draw if I never learned to draw?

My sister, four years older than me, was a very skilled drawer when we were kids; she had a very different artistic style than I did (or, at least, different from the aesthetic I aspired to), excelling at more caricature-like drawings. Still, she and I used to sit for hours drawing together, and I spent a lot of that time observing her and copying what she did and how she did it.

This is not too different from how I learned to write creatively. A voracious reader, my early attempts at writing copied plots, tone, and word choices from the books I read (sometimes verbatim!). By the time I was eight, I was even writing my own bio to go along with my stories, following the examples I’d seen on book covers.

When I was in high school, I wanted to learn to paint, and I got my first set of acrylics for Christmas in 1992. Below is the very first picture I painted with that set of acrylics: my dad napping on the couch (complete with his arm over his head and his feet sticking out of the blanket)!

I had never used acrylics before, had never painted on canvas panel before. I quite literally had no idea what I was doing, which may or may not be evident by looking at the picture, which was drawn freehand with charcoal. (I finally took my first acrylics painting class in 2023, which I write a bit about in this post.)

In 1999, I painted this leopard (below), using a photo from a library book as reference. This is a large painting, and it was the first time I had ever painted on stretched canvas, let alone something of this size. (It’s still one of my favorites.)

My painting technique improved over time—with practice, through trial and error, and by watching others, including an artist I started dating in 2000, whom I watched and learned from, much like I had with my sister many years earlier (he and I often painted together). But I really only learned about painting from him, not drawing.

I was still mostly just winging it, and often felt like I was an imposter, not a “real” artist.

And I still hadn’t learned how to draw.

What If I’m Doing It Wrong?

One thing that especially resonated with me during my drawing lesson this past week was when my teacher talked about how some people are self-conscious about their process/how they draw. You ask them to draw a cat, for example, and they can do it, in time, but they wouldn’t necessarily want anyone to witness their process.

Why? A lack of confidence. What if I’m doing it wrong?

Oh boy, could I relate! Around 2008, I was commissioned to do a painting of horses and given reference photos by a client; she had seen my leopard painting and several others hanging in my house. I completed the horse painting and she was pleased with the result, but any “real” artist would have surely cringed at my process. There were lots of “mistakes,” lots of erasing of pencil marks as I figured out what to paint where. (At the beginning of my drawing lesson, my teacher pointed out that I would not ever be using an eraser, which naturally brought to mind Bob Ross’s “happy accidents.” This was something I certainly didn’t understand in 2008!)

Similar to visual art (or, really, any skill), writers benefit from guidance or mentorship. My own writing improved by leaps and bounds once I learned how to study craft, which was something I was pretty clueless about until I started working on my MFA. Suddenly my writing process wasn’t as mysterious as it had previously been; there was suddenly some method to my madness (so to speak). Understanding the role of craft also gave me more insight into how to help others with their writing.

It wasn’t because I had previously been doing it “wrong.” More to the point: I didn’t fully understand what I didn’t know. We don’t know what we don’t know.

I often say that there is no one way to write, and I stand by that. You do not need art lessons to draw or paint, and you certainly don’t need an MFA to be a writer. But learning the building blocks to any art form can help you create on a different and possibly deeper level. (It’s also important to note that some things do come more naturally to some people than others. Not everyone needs the same level of instruction or the same amount of practice.)

Confidence, Consistency, and Efficiency

When you learn art—whether it be the “formula” for drawing or how to study the craft of writing, what you’re really doing is developing confidence, while also becoming more consistent (and therefore more efficient) as a creator.

And it often means letting go of what you previously knew, forgetting what you previously may have learned (or intuited). It may mean changing the way you approach a creative project.

This was definitely true for me with writing. As I became more confident and consistent in my creative writing (from studying craft), I found that I had to unlearn a lot, often arbitrary “rules” that well-meaning people had thrown at me over the years, which I had often tried to follow. Was I doing it wrong before? Not necessarily. But with more understanding, I could do it better, which, in my case, meant more consistency, more efficiency.

There's no one correct way to write, but what I often see, as both an editor and writing coach, is that a lot of writers lack confidence in their ability. It could be for a variety of reasons, but I suspect that at the heart of it, they are worried that they are doing it “wrong.”

It’s this lack of confidence, in fact, that often keeps talented writers from submitting their work to literary journals. I’m not a real writer. What if I’m doing it wrong?

The more you invest in your craft, either by reading, imitating others’ styles, or taking classes/workshops, the more inclined you are to feel like you know what you’re doing. That you’re worthy as a writer. And you are worthy as a writer, no matter what your inner self says. (And if you ever doubt yourself, I urge to read this old blog post I wrote in 2020: “Yes, You Are a Writer.”

Final Thoughts: What Is “Formula”?

One problem I have with the word “formula” (and the reason I put it in quotes) is that it implies ease and a certain kind of simplicity. In reality, the “formula” (for anything) is just a way to begin. A foundation to something larger and much more complex. Building blocks.

For example, many of us were taught the five-paragraph essay “formula” in school. It’s a reasonable “formula” to teach (and learn), but it’s by no means the end all to be all; in fact, it’s rudimentary at best. Very few real-life essays follow the five-paragraph formula. And what it ends up teaching a lot of students (unintentionally perhaps) is that writing is all about following a template.

It’s not.

The five-paragraph essay is simply a way to begin. In my drawing lessons, I’m starting with drawing cubes, but I will then (presumably) advance to drawing more complex things, e.g., fruit, faces, etc. The five-paragraph essay is like the cubes I drew during my first lesson. It’s a building block. Not a stopping point.

It’s only the beginning.

A very inspiring post, and I love the ongoing submissions + rejections count that you're doing, too! That's truly the only way to do it...I haven't done the 100-submissions-in-a-year thing yet, but when I managed to do 25 submissions in 2022, I got my first essay published in 2023. Dedication works!

Love the way you've analogized learning the craft of writing to learning the building blocks of drawing. I also appreciate you modeling so much openness to various things. Openness to the value of learning basics from the outside in, but also honoring the value of one's inside-out process, even without formal instruction. Hope you continue to enjoy the drawing lessons!